AWS Lambda is famous service that has popularized the idea of serverless in cloud computing. It was not the first service of a kind, nor the last, but definitely was, and remains, the most popular and widely used. In this article we will take a closer look on the anatomy of the AWS Lambda functions and the processes that are happening below the surface.

It's a long article, but hopefully interesting. If you however prefer to just view some particular topic, use the table of contents below.

- What is Serverless

- Lambda

- Lambda execution in details

- Concurrency

- Invocation methods

- Roles and permissions

- What's under the hood?

What is Serverless?

One cannot discuss Lambda without discussing the serverless architecture, one is driven by another. There are many definitions but in short: Serverless architecture allows you to focus entirely on the business logic of your applications. You don't have to think about servers, provisioned infrastructure, networking, virtual machine etc. All this stuff is handled for you by a cloud provider (AWS in case o Lambda). Usually it means, that your application heavily relies on managed services (like Lambda, DynamoDB, API Gateway) that are maintained by a cloud provider and allow you to abstract the server away.

Serverless services are usually characterized by following capabilities:

- No server management – You don’t have to provision or maintain any servers. There is no software or runtime to install, maintain, or administer

- Flexible scaling – You can scale your application automatically or by adjusting its capacity through toggling the units of consumption (for example, throughput, memory) rather than units of individual servers

- High availability – Serverless applications have built-in availability and fault tolerance. You don't need to architect for these capabilities because the services running the application provide them by default

- No idle capacity – You don't have to pay for idle capacity. There is no need to pre-provision or over-provision capacity for things like compute and storage. There is no charge when your code isn’t running.

AWS provides us with many serverless services: DynamoDB, SNS, S3, API Gateway or the fairly new and extremely interesting AWS Fargate. But this time w will only focus on AWS Lambda, a core service of a serverless revolution.

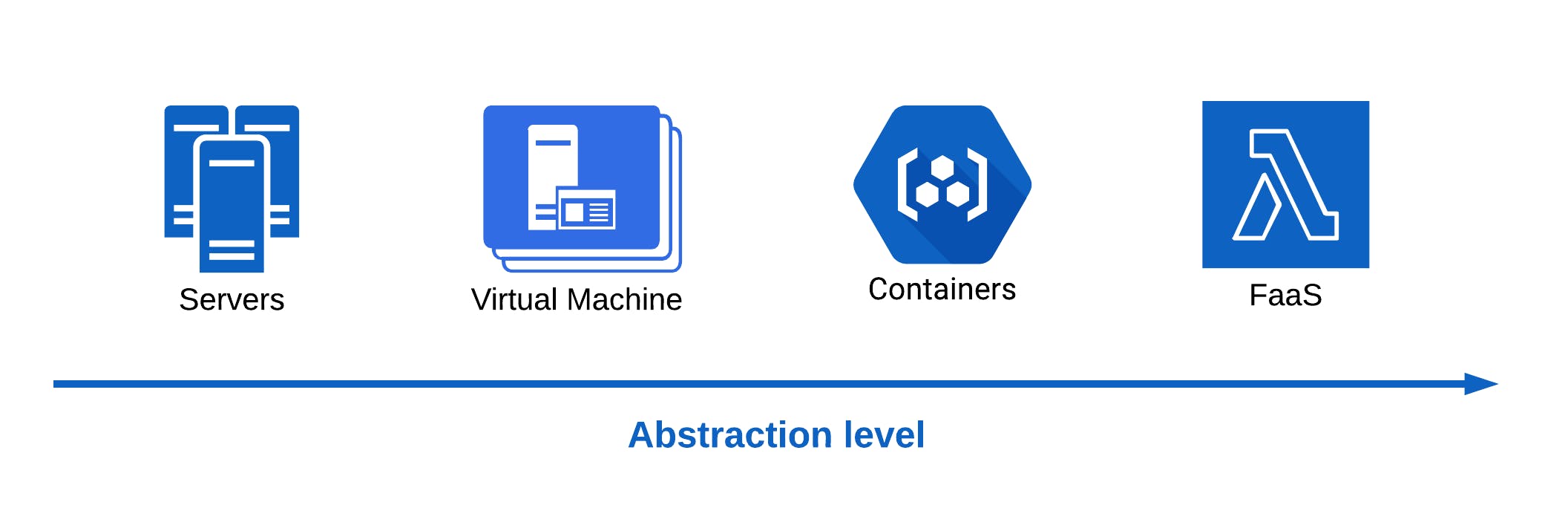

Lambda - no servers, just code

Lambda can be described as Function as a Service (FaaS), where the functions is the main building block and execution unit. No servers to manage, no virtual machines, clusters, containers, just a function created in one of the supported languages. As with any other managed service, provisioning, scaling and reliability is handled automatically by AWS. This allows us to work on a very high abstraction level, focus entirely on the business logic and (almost) forget about underlying resources.

Basic Lambda Example

Let's take a look at a simple lambda example.

exports.handler = async function(event, context) {

console.log('Hello Lambda!');

}

You can see that we've defined so called handler, the function that will be executed by Lambda Service, every time the event occurs. Handler takes two arguments: an Event object, and a Context. We will take a closer look at those later.

You might have noticed, that we've defined our handler as an async function, this allows us to perform asynchronous operations inside Lambda handler. By returning a promise as a result of handler call, we not only are able to return a result of asynchronous operation, but also we make sure that the Lambda will "wait" till all the started operations are finished.

You don't have to use asyn/await syntax or promises at all, if you prefer "old school" callback approach, you can use a third handler argument:

exports.handler = function(event, context, callback) {

/// ... async operations here

callback(asyncOperationResult);

}

Lambda is an event driven service, every lambda execution is triggered by some event, usually created by another AWS service.

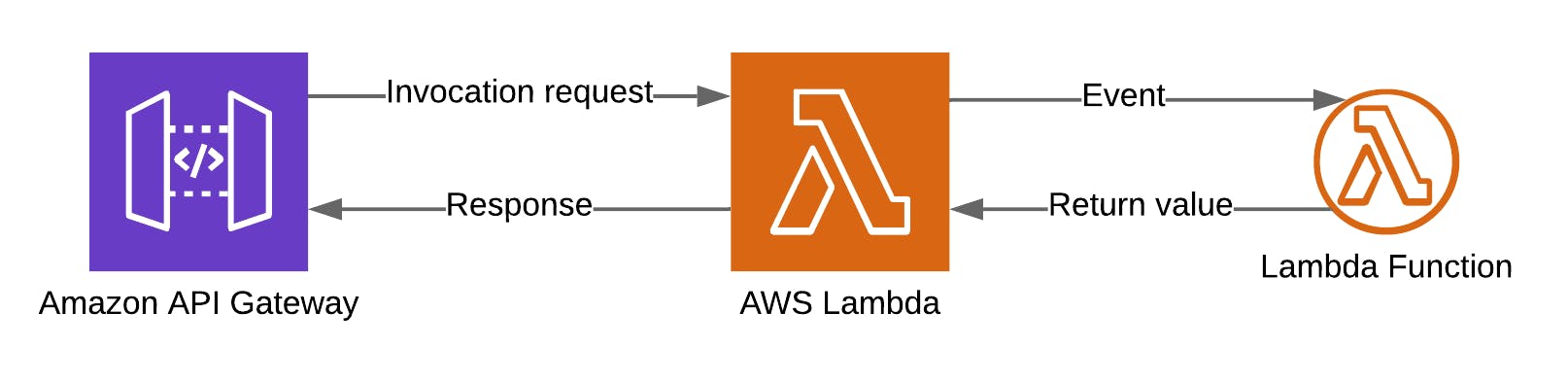

An example of a compatible event source is API Gateway, which can invoke a Lambda function every time API Gateway receives a request. Another example is Amazon SNS, which has the ability to invoke a Lambda function anytime a new message is posted to an SNS topic. There are many event sources that can trigger your Lambda, make sure that you check the AWS documentation for the full list of those.

Event and Context

Every Lambda function receives two arguments: Event and Context. While Event provides function with the detailed information about the event that has triggered the execution (for example, Event from API Gateway can be used to retrieve request details such as query parameters, header or even request body).

exports.handler = async function(event, context) {

console.log('Requested path ', event.path);

console.log('HashMap with request headers ', event.headers);

}

Context on the other hand, contains methods and properties that provide information about the invocation, function, and execution environment (such as assigned memory limit or upcoming execution timeout).

exports.handler = async function(event, context) {

console.log('Remaining time: ', context.getRemainingTimeInMillis());

console.log('Function name: ', context.functionName);

}

Lambda execution in details

You might have noticed, that our lambda code can be divided in two parts: the code inside the handler function, and the code outside of the handler.

// "Outside" of handler

const randomValue = Math.random();

exports.handler = function (event, context) {

// inside handler

console.log(`Random value is ${randomValue}`);

}

// this is still outside

While this is still the typical JavaScript file here, those two parts of code are called differently, depending on the Lambda usage. But before we dig in to this topic, we have understand one crucial thing regarding Lambda functions: Cold Start and Warm Start.

In order to understand what's behind Cold Start and Warm Start terms, we have to understand how our Function as a Service works.

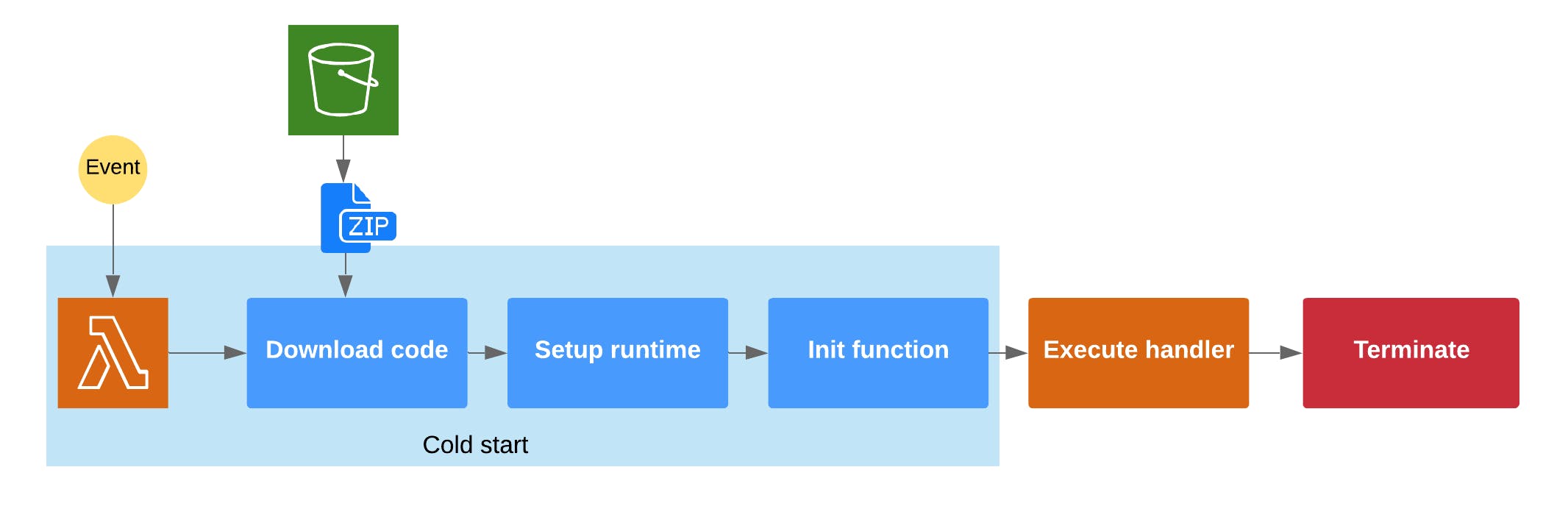

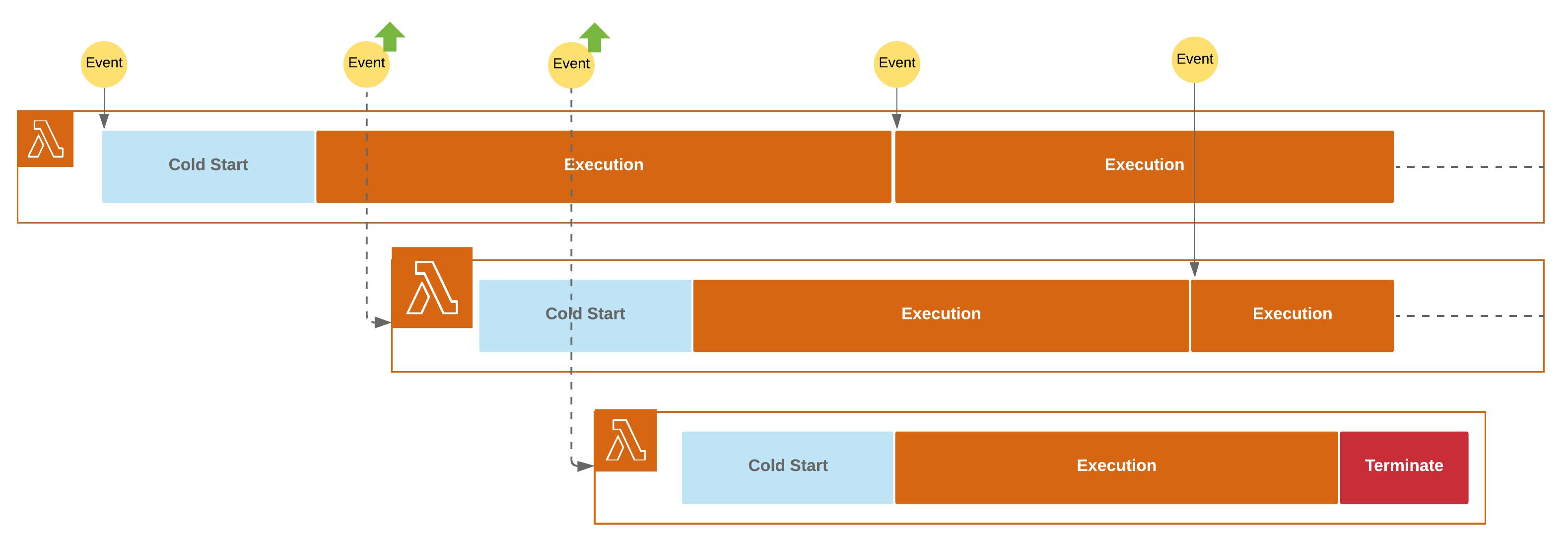

Cold start

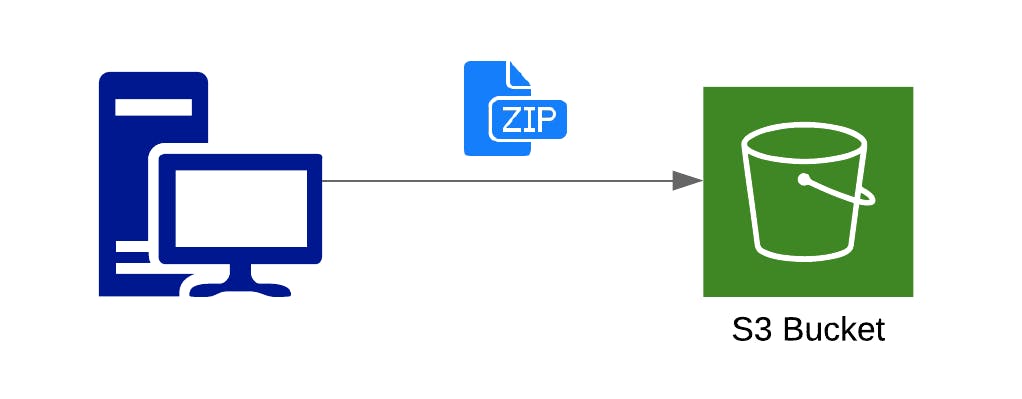

In the idle state, when no events are being fired and no code is being executed, your lambda function code is stored as a zip file, a lambda code package, in an S3 bucket. In case of JavaScript, this zip file usually contains a js file with your function code and any other required files.

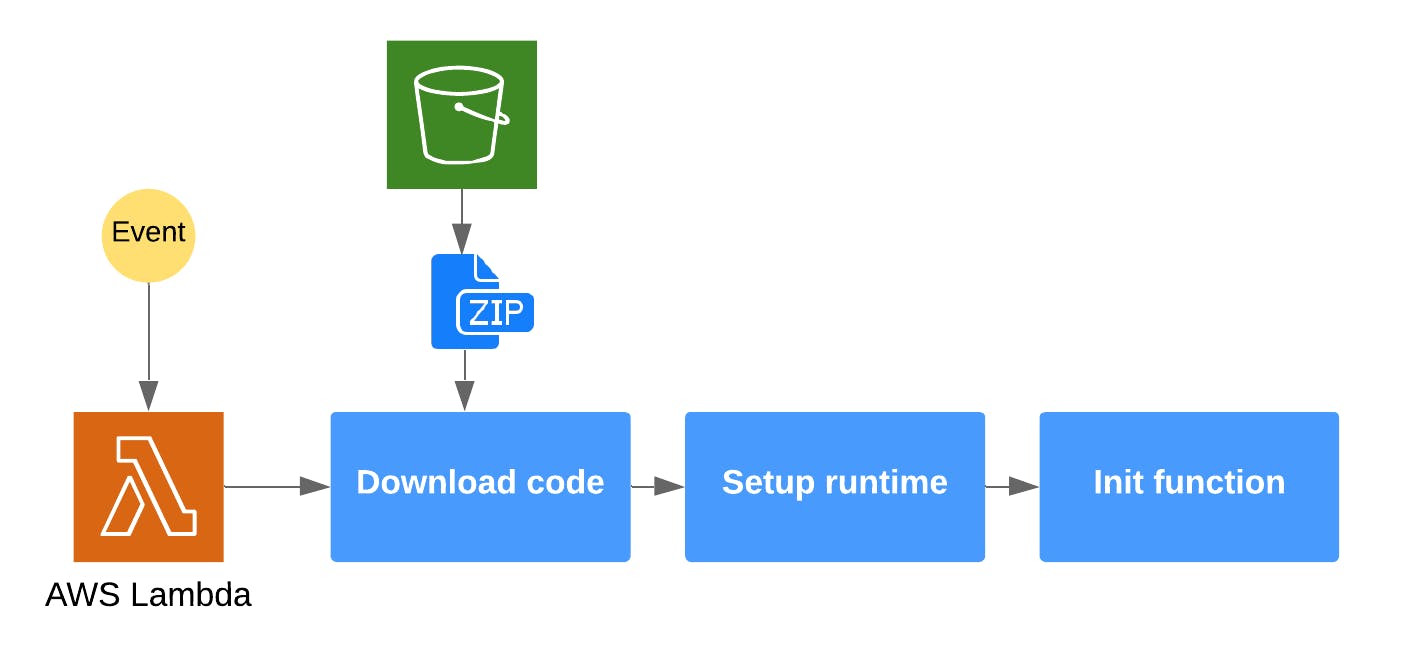

Once the event occurs, Lambda has to download your code and set up an runtime environment, together with the resources specified in the Lambda configuration. Only after this step, your lambda code can be executed.

This process is so called Cold Start of Lambda function, it happens when your Lambda is executed for the first time, or has been idle for a longer period of time.

Only after the initial setup is finished, you handler can be executed, with a triggering event passed as an argument.

The exact length of the Cold Start varies, depending on your code package size and settings of you Lambda function (functions created inside your private VPC usually have longer cold starts). You should be aware of this if the long cold start can affect users of your service. For that reason it's wise to keep you code package size as small as possible (be mindful about node_modules size!) and to select a runtime that provides faster cold starts.

Ok, so what about Warm Start?

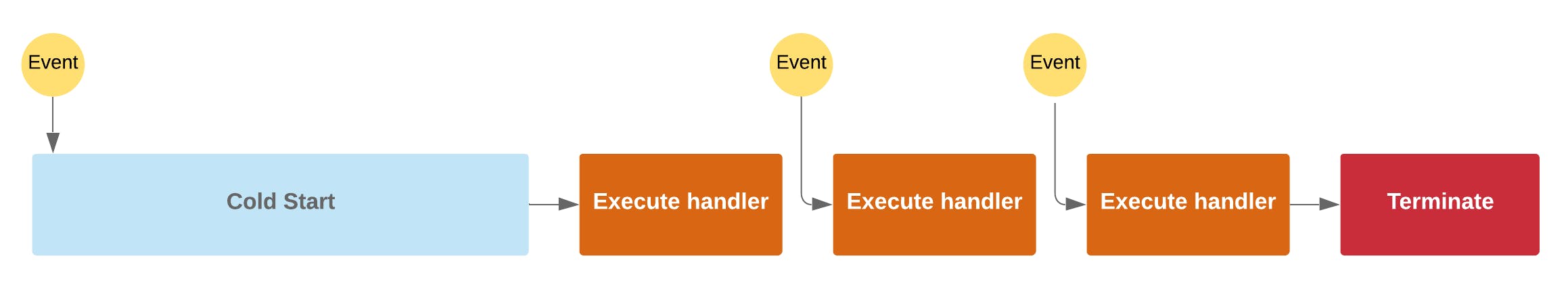

Warm start

The runtime described above is not terminated immediately after handler execution. For some time, the runtime remains active and can receive new events. If such event occurs, the warm runtime does not have to be initialized again, it can execute the handler immediately.

Warm execution is of course much much faster then the cold one. However, the problem is that we cannot assume that the function will, or will not be called with a cold or warm start. The time for which the function stays warm is not precisely defined in the documentation and is actually based on your configuration and actual Lambda usage. What's more, if you allow concurrency of your Lambdas, newly created Lambda instances will also start with a cold start. This means that you have to mindful of the above processes, and try to optimize both your cold and warm starts.

Initialization vs handler

And how does this affects our code? Remember our example of a handler function?

// "Outside" of handler

const randomValue = Math.random();

exports.handler = function (event, context) {

// inside handler

console.log(`Random value is ${randomValue}`);

}

// this is still outside

The code outside of the handler function is executed ONLY during cold start. Handler function on the other hand, is executed for every event.

// This will be executed only during cold start

const randomValue = Math.random();

exports.handler = function (event, context) {

// Handler will be executed for every request

// So, what will be displayed here?

console.log(`Random value is ${randomValue}`);

}

Handler can still use all the variables created during the initialization, since those are stored in the memory (till the runtime is terminated). This means, that in the above code snippet, randomValue will be the same for every handler call. While this is probably not what we've wanted to achieve, using cold / warm start phases we can apply some optimization in our code.

In general, it's recommended, to store all the initialization code outside of the handler function. All the initialization (like creating database connection), should be done outside of handler and just used inside it.

const config = SomeConfigService.loadAndParseConfig();

const db = SomeDBService.connectToDB(config.dbName);

exports.handler = async (event, context) => {

const results = await db.loadDataFromTable(config.tableName);

return results;

}

This way we not only vastly improve the execution time of our handler, but also we make sure that we are not hammering our DB with a new connections being created per every lambda invocation.

There are many advanced optimization techniques that we can apply to our lambda functions. Still, being aware of cold and warms starts and a code optimization based on those processes is a simple and very efficient approach that you should apply by default to all your lambdas.

Concurrency

Even the most optimized services have to scale, in order to handle heavy workloads. In "classic" applications, this is handled by auto scaling group, that is responsible for tracking the servers utilization and properly provisioning additional servers when needed (or terminating unused ones). But when using Lambda, we don't work with servers, so how can we scale our function?

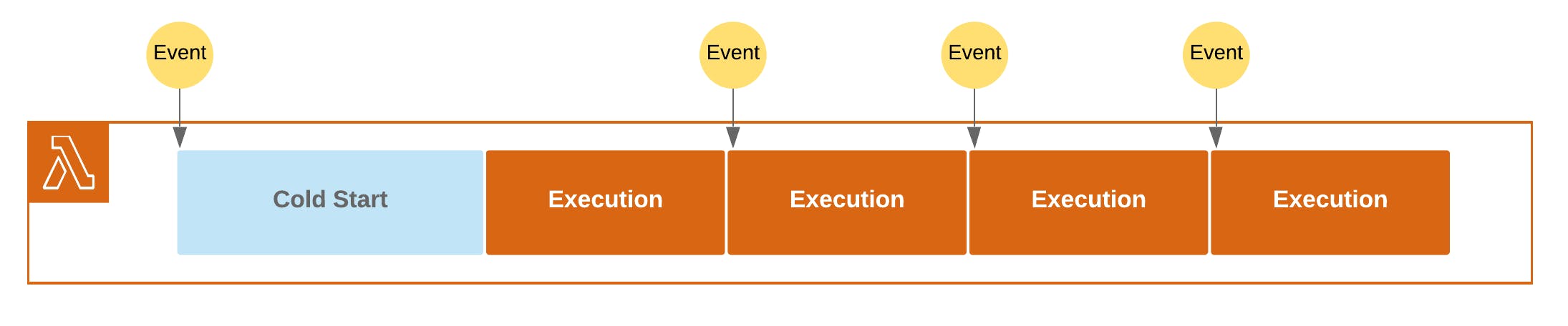

Scaling logic in Lambda

As we might expect, auto scaling of Lambda functions is handled automatically by Lambda service.

By default, Lambda is trying to handle incoming invocation requests by reusing the existing warm runtimes. This works if the function execution time is shorter then the time between upcoming requests.

This is a very reasonable approach both from our point of view (warm runtime means faster execution time and ability to reuse resources and connections) and for AWS (service does not have to provide additional runtimes).

However, if the time between the events is shorter then the function execution time, the single function instance is not able to handle those invocation requests. In such cases, to handle the workload, Lambda has to scale.

If Lambda receives a new invocation request while all the current runtimes are busy, it will create another runtime. This new runtime will handle the upcoming invocation request and execute the function code. Then runtime remains in the warm state for some time and can receive new requests. If the runtime stays idle for a longer period of time, Lambda terminates it to free the resources.

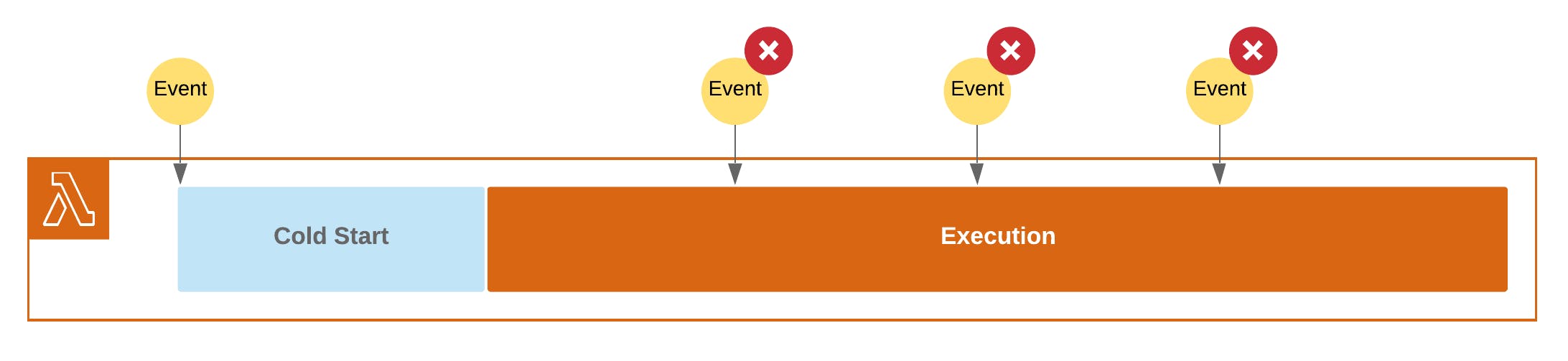

Concurrency limit

There is a concurrency limit applied to every Lambda function, it specifies the maximum number of runtimes created at the same time. If your function starts exceeding this limit, the upcoming invocation request will be throttled. In most cases AWS Services that trigger Lambdas, are able to detect this situation and retry the request after some time.

So, since we can modify the concurrency limit of our Lambdas, is there any reason we should set up a low concurrency limit?

Yes, and this is actually quite a tricky use case. Remember that every Lambda runtime is isolated, which means that resources are not shared across those. If your Lambda connects to some Database, every runtime has to create a separated DB connection.

In case of a high concurrency limit, this is a dangerous situation, since your DB can simply be DDOSed by a 1000 incoming connections in a very short period of time. In such situation it's better to set up a low concurrency limit (or just change the database to the one that can handle such workloads).

Now, let's take a bit more detailed look about different Lambda invocation methods.

Invocation methods

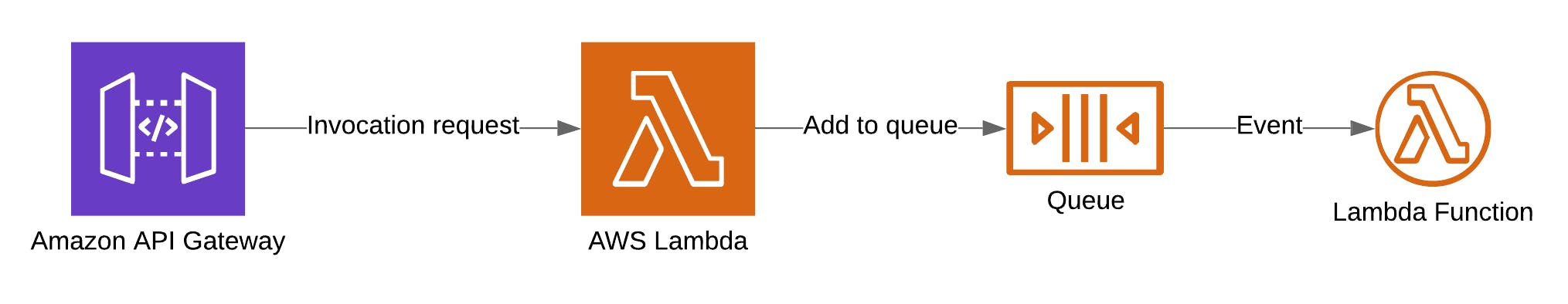

Push vs Pull

Lambda can be invoked in two different ways:

- Push invocation model - Lambda function is executed when a specified event occurs in one of the AWS services. This might be a new SNS notification, new object added to S3 bucket or API Gateway request

- Pull invocation model - Lambda pulls the data source (might be SQS queue so called Event Source Mapping) periodically and invokes your lambda function passing the batch of pulled records in an event object

The above invocation model does not change a lot in terms of your function code, but you should be aware of it, when calculating the cost of you Lambda or architecting the data flow. Especially the second model, pull invocation, might create some confusion. You might be expecting the Lambda to be called immediately when new message is posted to SQS, while in fact, SQS will be periodically pulled and you function will receive a whole batch of recently added messages.

Synchronous vs Asynchronous

Additionally, the function can be called using two different invocation types:

- RequestResponse - function is called synchronously, the caller waits for the function to finish and return the result. For example APi Gateway uses this invocation, which allows it to retrieve a request response object from Lambda.

- Event - function is called asynchronously, and caller does not wait for the function to return the value. The event is being pushed to the execution queue where it will wait for the function execution. This invocation type can automatically retry the execution if the function returns an error.

In real world, the invocation type is usually defined by the service that creates the event and calls the lambda functions.

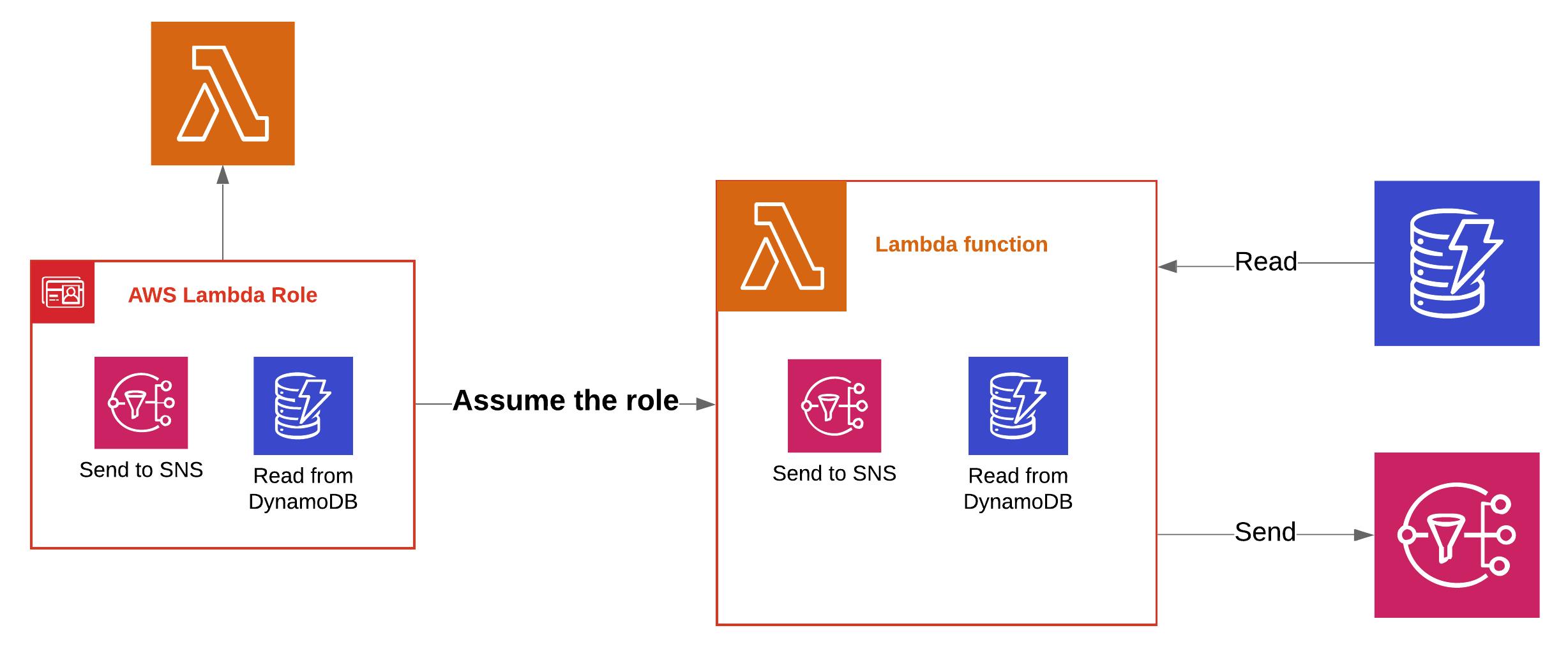

Roles and permissions

One of the biggest advantages of Lambda is the fact that it's integrated with AWS IAM - a service that is responsible for managing permissions of your AWS resources. As with everything related to IAM, detailed permissions management for AWS Lambda is quite a complex process, for the most part however, it resolves around an execution role.

Execution role

Execution role is a role that your lambda function assumes when it's being executed. But what does it actually means?

The IAM role is a collection of permissions, you can have a role that for example is permitted to read and save the data to some specific DynamoDB instance. When you assign this role to your Lambda function, it will assume this role when invoked. As a result, during the execution, Lambda will run with a set of permissions defined in the role.

One role can be assigned to multiple lambdas, which is convenient if they require the same set of permissions. Remember however, that you should always only grant Lambda the minimum set of permissions required for it to work properly, therefore having one role, with all the permissions, shared by all the lambdas, is not a good idea.

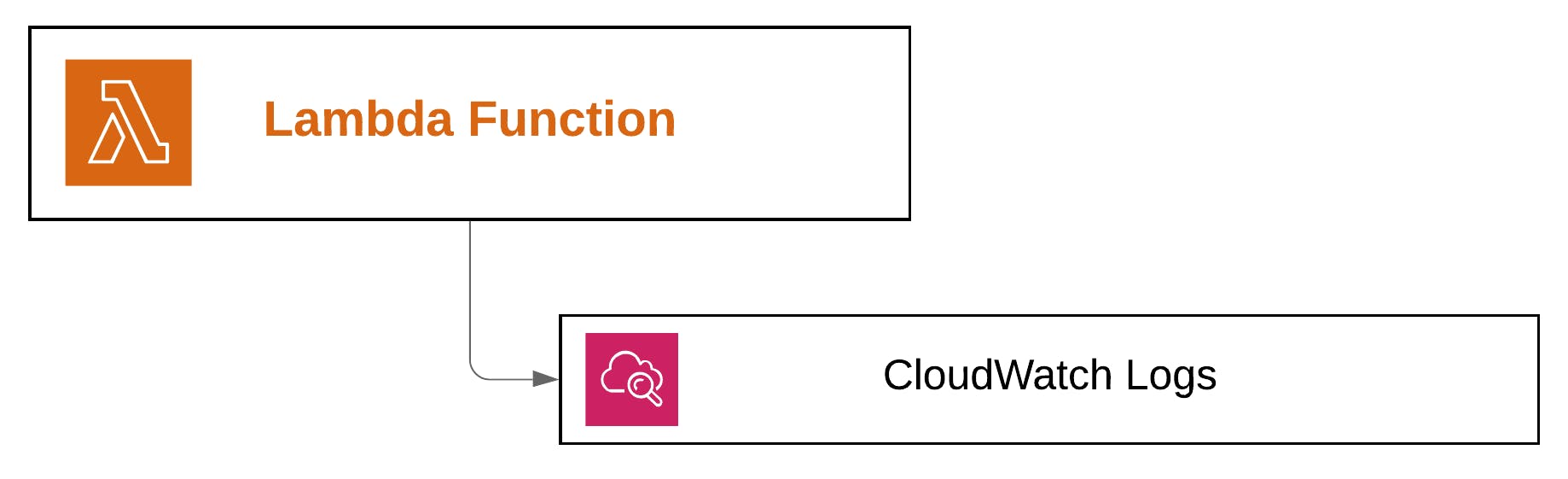

At a minimum, your function needs access to Amazon CloudWatch Logs for log streaming, but, if your function is using a pull invocation model, it requires additional permission to read the data source (for example to read messages from SQS queue).

Example of a simple role

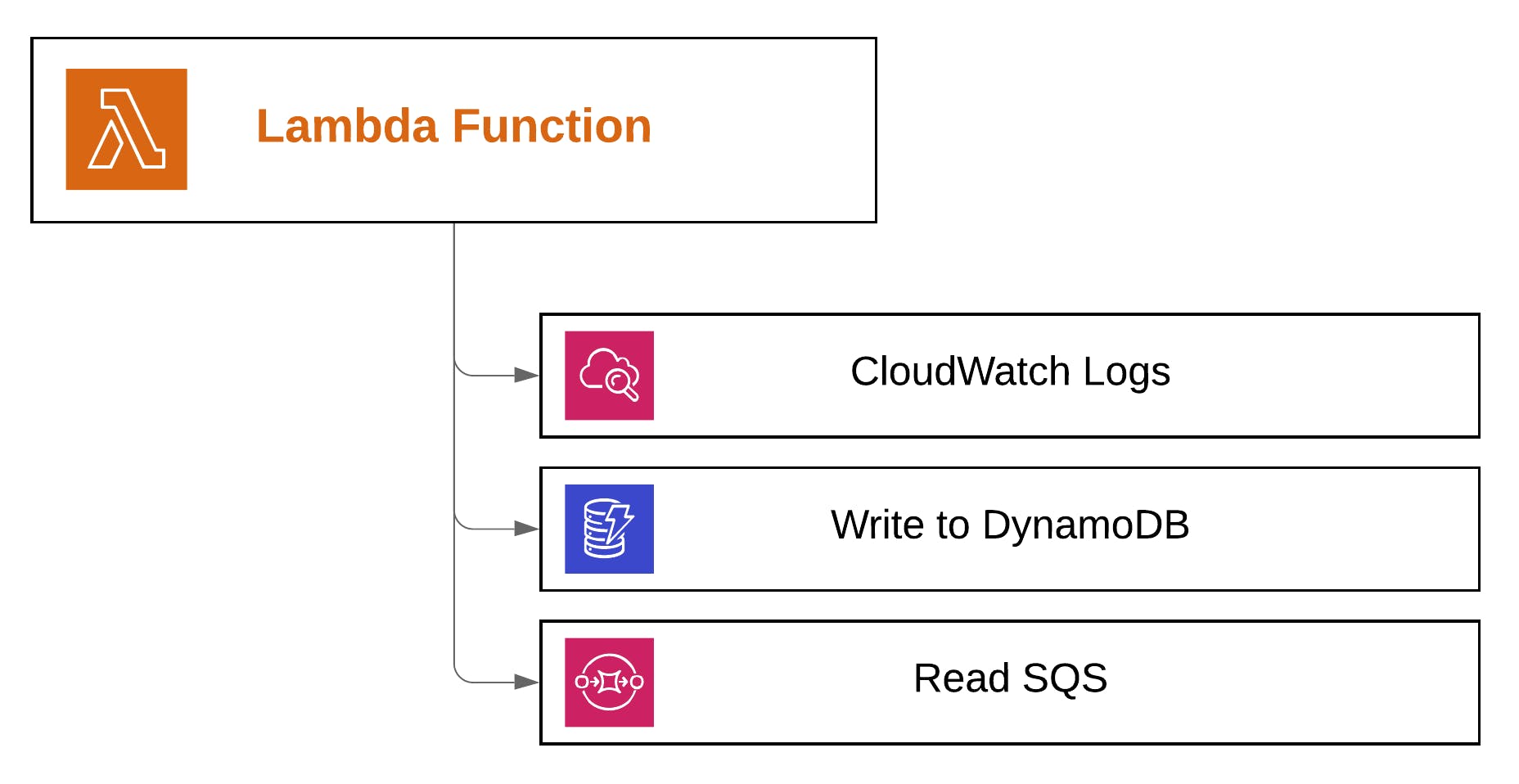

Let's assume that we want to create a Lambda function that reads the SQS Queue, process the data and saves the results to DynamoDB table. What should be the definition of the execution role for this function?

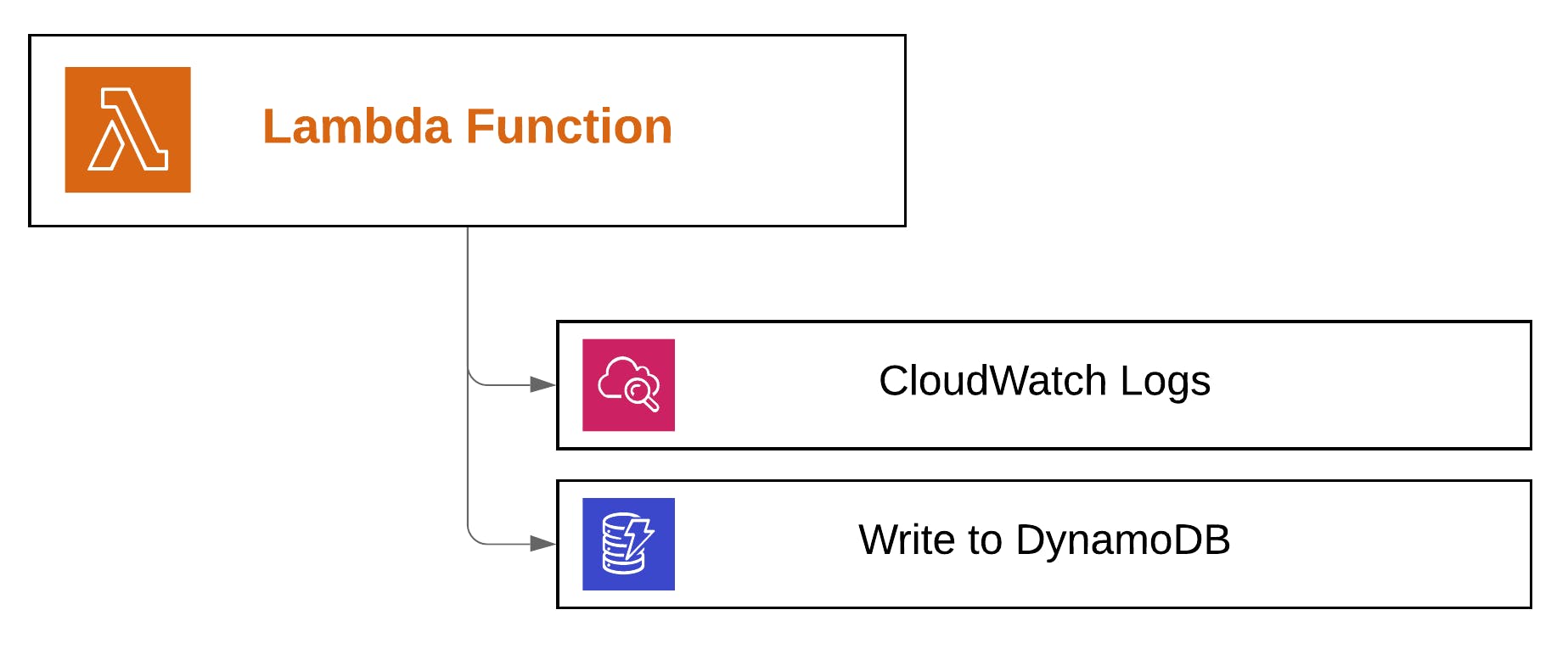

First of all, the service needs a permission to send logs to CloudWatch, this allows us to monitor and debug our application if needed.

Since, it's going to write data to DynamoDB, we have to add a proper write permission as well

Should we add a read permission as well? Assuming that our lambda only writes the data to DB, no. That's the "minimum required permission" rule, if the permission is not absolutely needed, don't use it.

As a last step, we have to add a permission that will allow our Lambda to read SQS queue. As stated above, Lambda needs to be able to read the awaiting messages in order to provide those to our Lambda function during execution.

This set of permissions will allow our Lambda to successfully perform the task it was designed for... and nothing else. And that's exactly what we wanted to achieve.

What's under the hood?

Lambda provides us with the amazing set of functionalities, and the biggest advantage of this service is that we don't have to think about the servers and all the technology under the hood that powers it. But we are very curious creatures, right? So, when our functions are executed, what is actually happening behind the curtain?

The details of Lambda technology would require a whole separated article (or a book...), but in general, we can try at least scratch the surface here.

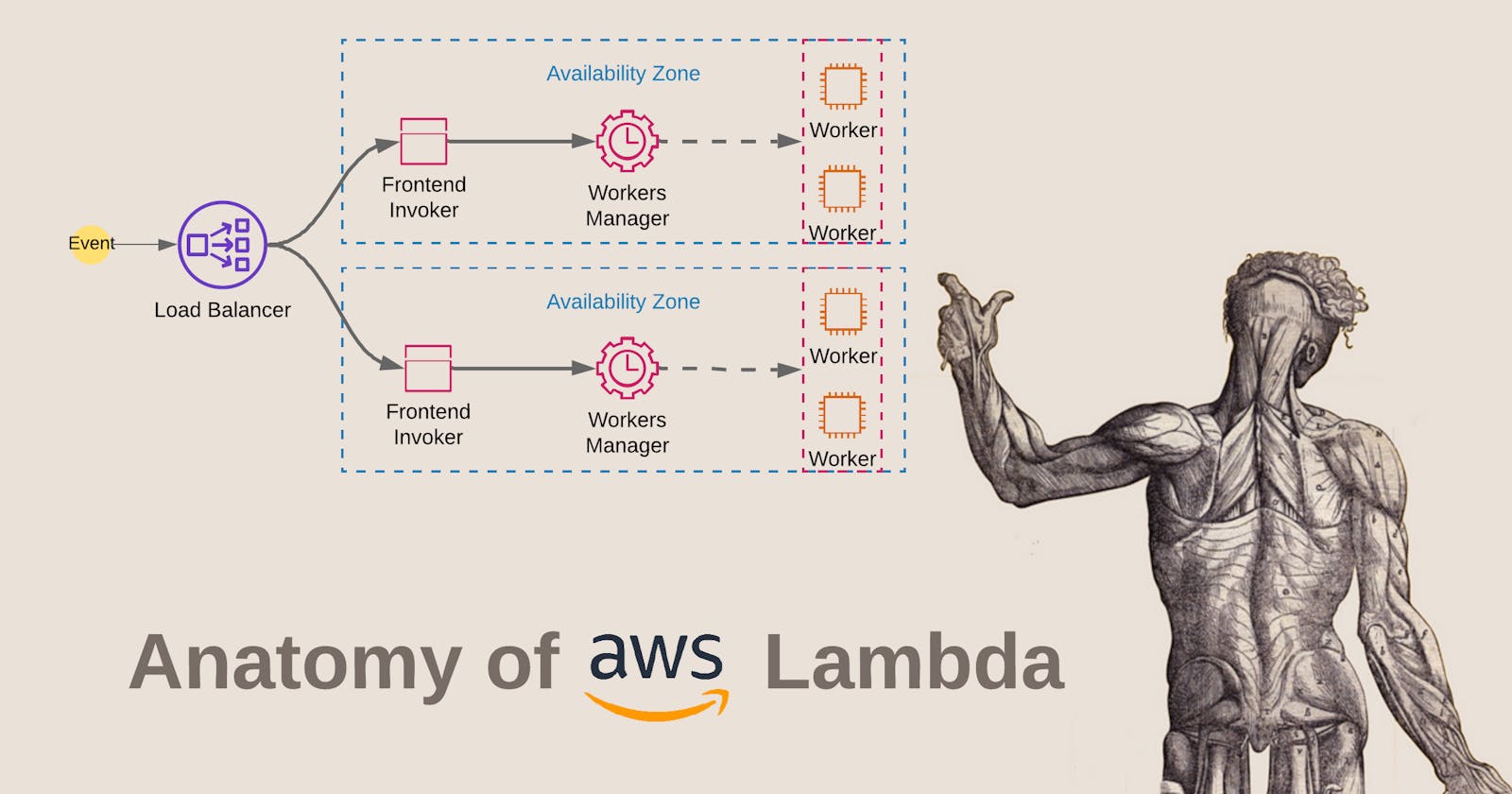

Lambda invocation flow

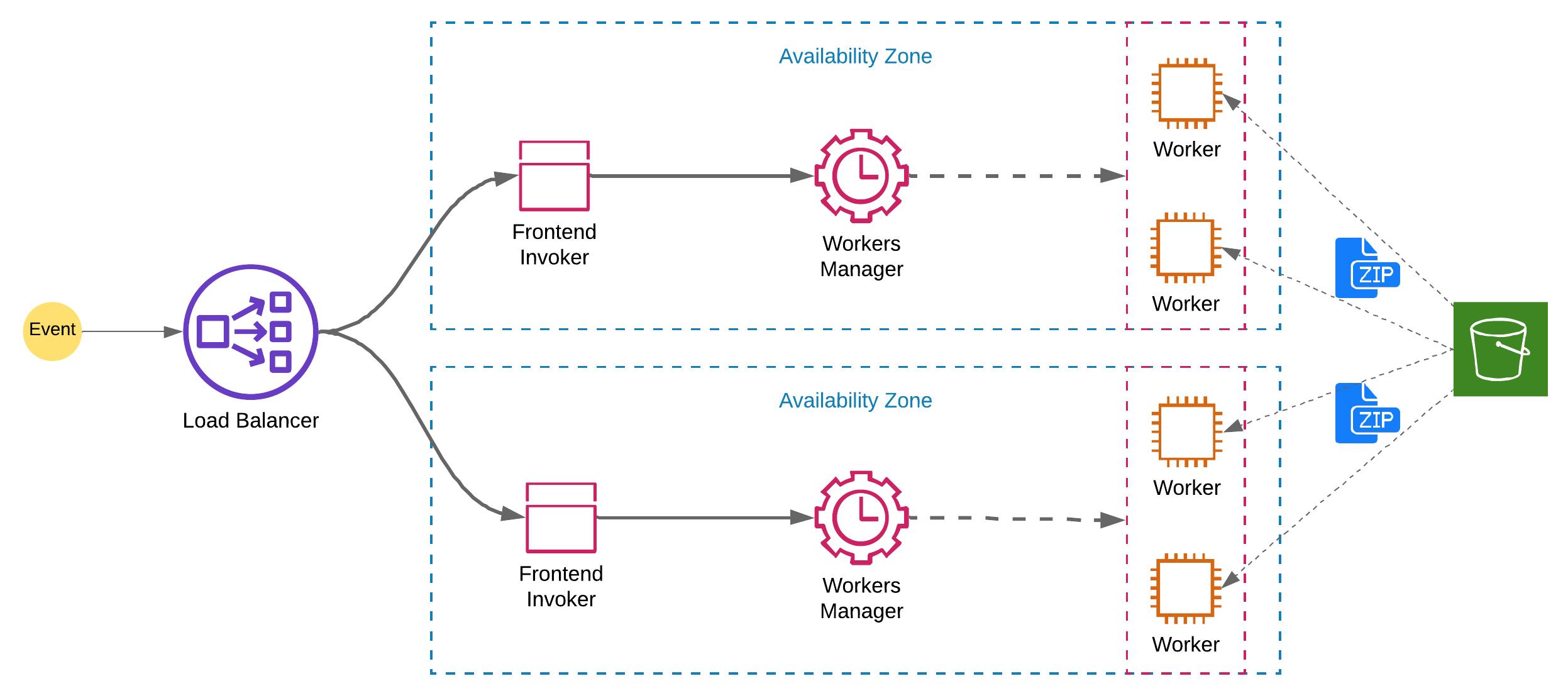

Lambda service is in fact a whole set of services cooperating together to provide the full range of Lambda functionalities.

- Load Balancer responsible for distributing invocation requests to multiple Frontend Invokers in different Availability Zones. It is also able to detect the problems in a given AZ and route the request to remaining ones

- Frontend Invoker is a service that receives invocation request, validates it and passes it to the Worker Manager

- Worker Manager is a service that manages Workers, tracks the usage of resources and sandboxes in Workers and assigns the request to a proper one

- Worker provides a secure environment for customer code execution, this is the service responsible for downloading you code package and running it in a created sandbox.

- Additionally there is a Counter service responsible for tracking and managing concurrency limits and a Placement Service, that manages sandboxes on workers to maximize packing density.

Summing up, the invocation request is passed by Load Balancer to a selected Frontend Invoker, Frontend Invoker checks the request, and asks the Worker Manager for a sandboxed function that will handle the invocation. Worker Manager either finds a proper Worker and a sandbox, or creates one. Once it's ready, the code is executed by a Worker.

Isolation

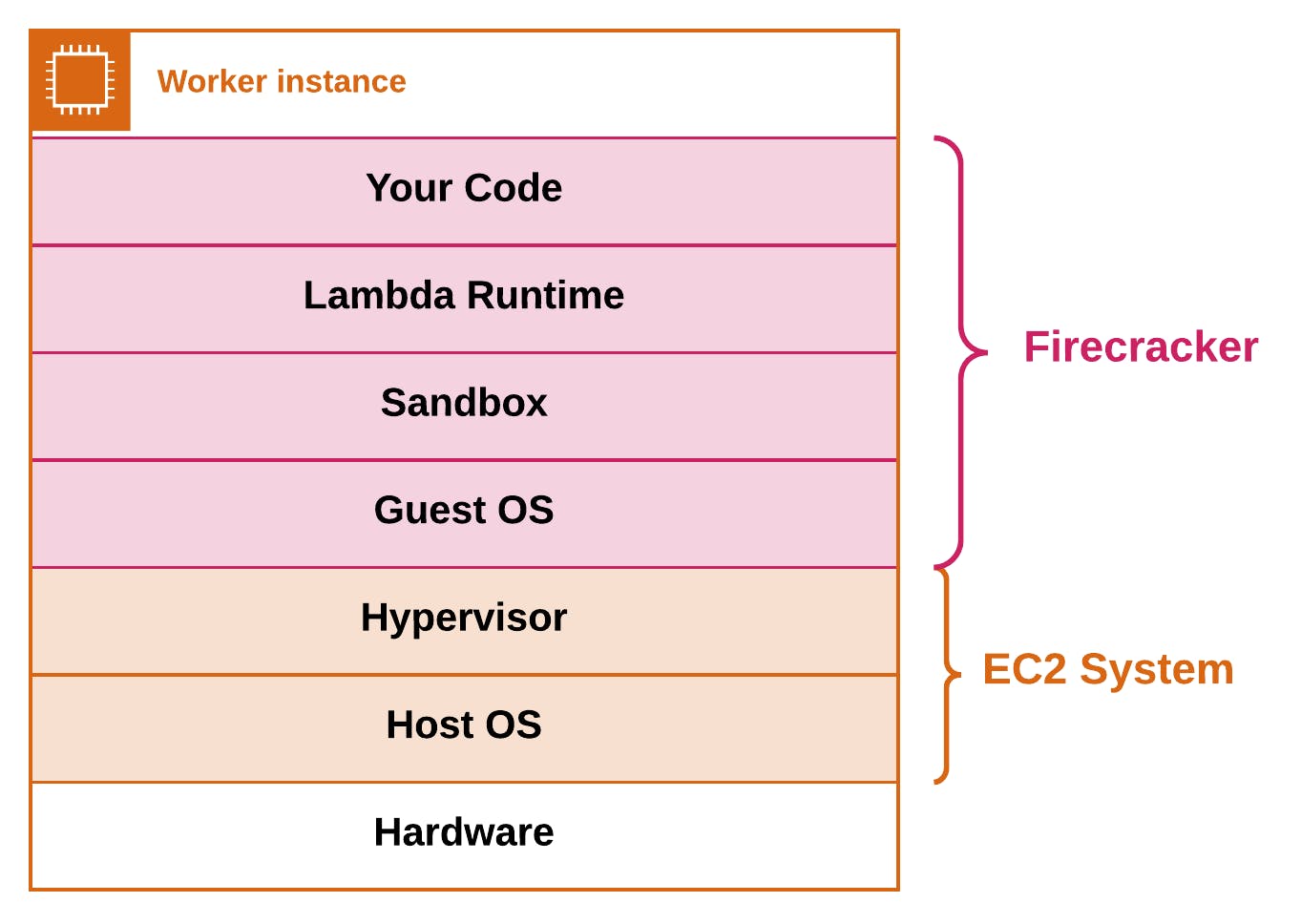

Worker is usually some EC2 instance running in the cloud. There can be multiple different functions, from different users running on the same Worker instance. To keeps things secure and isolated, every function runs on a secure sandbox. Single sandbox can be reused for another invocation of the same function (warm runtime!) but it will never be shared between different Lambda functions.

The technology that powers this flow is Firecracker. It's an open source (link) project that allows AWS to span hundreds and thousands lightweight sandboxes on a single Worker.

Since sandboxes can be easily and quickly created and terminated, while still providing a secure isolation of functions, Workers can be reused across multiple Lambdas and even Accounts, which allows the Placement Service to organize the work to create and apply the most performant usage patterns as possible.

The above is a very brief and simplified overview of Lambda internals, if you would like to get some more fascinating details, check this talk from re:Invent

Conclusion

Thank you for reaching the end of this article. It has gotten quite long :) Still, hopefully it was an interesting overview of what's Lambda and how to work with it. If you are interested in more details, just contact me!